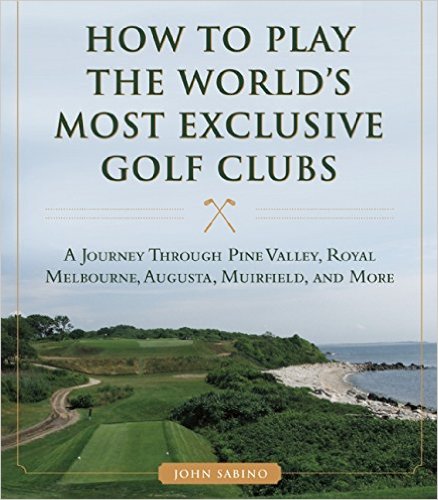

Hope springs eternal, and I'm hopeful to see this in person in April

Entering the alien world of cancer treatments was an eye-opening experience at all levels. I have been a long-time reader of the works of Atul Gawande, an Oxford and Stanford educated surgeon and Harvard Medical School professor who writes for the New Yorker. He espouses the importance of following a defined protocol and of a seemingly trivial thing: using checklists. He espouses it for the same reason Sully Sullenberger and Jeff Skiles immediately went to their emergency checklist after hitting a flock of birds after taking off from LaGuardia Airport. Because they work.

Maybe Bryson DeChambeau is on to something with his scientific and methodical approach to the game. He is continually rising on the money list with his checklist approach to golf.

One of the reasons I had great care around the clock is that everyone was reading from the same playbook and religiously followed their procedures and checklists. Even if each individual practitioner is of the highest caliber, the system is only as good as its weakest link. The way they all worked together on an integrated basis and handed off seamlessly from shift-to-shift is because they follow their protocol. This was an eye-opening lesson for me.

Although I was in a fog, during those first few hospital days I noticed that the doctors kept saying that I would hit “nadir” on about day 14 of treatment. I wasn’t exactly sure what nadir meant since this isn't the kind of word we typically use in Jersey. My closest prior association with the word Nadir is the activist Ralph. I ended up getting a master class in the meaning of nadir during my initial hospital stay. In retrospect, the reason that use such a fancy term is so they don’t scare the hell out of you. Nadir means hitting rock bottom. Everyone at the hospital works really hard to keep the environment upbeat. Using phrases like “rock bottom” or “crashing” don’t fit the construct.

I also learned during my trial by fire that it’s not the disease that necessarily kills you, sometimes it’s the treatment or side effects. My initial induction chemo included three different drugs and their side effects were far ranging. The evil nemesis that got me is a dastardly condition called mucositis. The

Nadir for me was when they transferred me off the specialty oncology floor and into intensive case. If the hospital environment itself was an alien environment, the ICU is the real-world version of being in a Twilight Zone episode. It’s a high stress environment that is crowded, has bad light and acoustics, and poor air. There are a lot of monitors and nothing to eat. Come to think of it, it’s a lot like traveling through Terminal A at Newark Airport.

Unlike a regular hospital floor, there is no idle chatter or banter among the practitioners.The doctors and nurses in ICU behave like Tiger does when holding the lead in a tournament. It’s game day and everyone has their game face on all the time. My doctors were baffled by my particular set of symptoms so they assembled a multi-disciplinary team to discuss my case. It was truly a surreal scene. Due to my condition I couldn’t speak, but I could see ten doctors assembled around my bed in a “U” formation and they spoke of me as if I weren’t there. The team included a pharmacist, my oncology team, and specialists from Infectious Disease, ENT, Allergy, Radiology, Neurology, Gastroenterology and Intensive Care. It seemed like every department was weighing in except the Obstetrics and Gynecology team, although I was in such a daze they could have been there too and I just missed them.

Even with all that firepower they couldn't figure out what precipitated my rapid demise. I will spare you the gory details, but the ICU doctors saved my life. I had to be intubated first through the nose (not for the faint of heart) and then when there were complications, through the mouth, and it was touch and go for a while. God bless everyone who helped save me and “the wife,” who literally stood by my bed for 72 straight hours. It's affirming to recount the story now, after the fact, with a good outcome, but I can assure you in the moment, when you have that many talented people trying to identify the problem and failing to come up with a definitive answer, it is terrifying.

As if I didn’t have enough problems with the cancer, one of the consequences of being in ICU for three days is that I came back to the oncology treatment floor a basket case. Since I couldn’t eat, they had to feed me something that looked like wallpaper paste intravenously (it’s called TPN). It turns out that TPN has a lot of sugar in it, so I developed diabetes. In addition to all the other IV medications and pills I was taking, I had to be pricked several times a day to have my blood sugar level checked and given an insulin shot in the stomach to correct any imbalances. I began May looking like a poorly aging version of Keith Hernandez. In a short period of time I was doing a pretty good impression of a fasting Mahatma Gandhi: mustache still intact, but bald and frail, my days spent largely in bed while occasionally shuffling around in a white sheet.

Ever the optimist, rather than viewing the debacle I went through as problematic, I felt lucky to be in the care of such experienced and determined people who excelled at what they do.

Since I spent the entire month of May in my room, which overlooked the University’s central quad, I got to watch the preparation for the graduation festivities and to dream of one day getting better and being able, first, just to go outdoors, and then, of being able to golf once again. Barring further complications, I’m still hopeful that things can come together and that “the wife” and I will make it to the Masters this year.

Post Script - For the physician readers among my followers, two weeks after the incident I got a visit from the Allergy doctor, a professor at Penn who was part of the bedside huddle. Frustrated by not being able to help, he wouldn't let my case go and went away and did research in the medical textbooks. After reviewing my blood work from the time he concluded that I had a rare condition called 'acquired angioedema' brought on by the leukemia, and he found a specialty medicine to treat me if the condition ever returns.

We live in a time of heightened animosity across many parts of our life these days, especially in the political arena. The cable news driven tribalism that is dividing us is troubling. It is easy to become cynical and have a lack of trust. This is a busy guy, he could have easily gone on to other things after my condition passed. He didn't, which is encouraging to say the least. He is just one small example of people who go above and beyond and shows there are plenty of good hearted, caring souls among us. Among other life lessons he reinforced, such as, persistence matters, he has helped reorient me to focus on the positive and not the negative, something that is increasingly difficult to do in the negative media environment we live in.