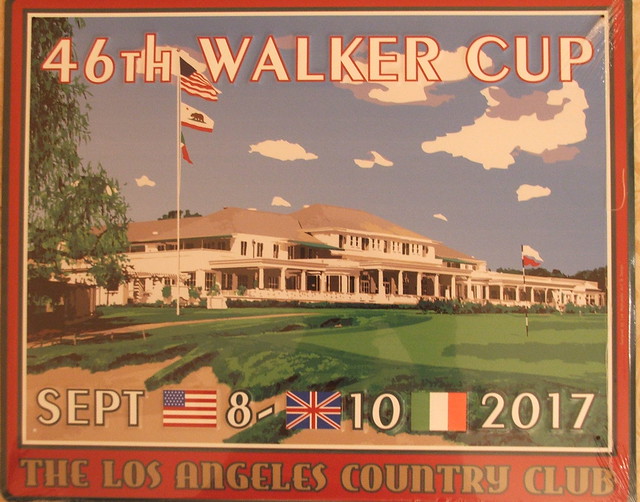

The 2017

Walker Cup, conducted over the North Course at the Los Angeles Country Club (LACC) this past September, was the latest episode of one of the greatest sporting events

ever. The event celebrates amateur golf, and it is deeply rooted in the aristocratic

traditions of the early game. The event was first announced at the Waldorf

Astoria Hotel in New York in January 1921. The occasion was the U.S.G.A.’s

annual meeting, and George Herbert Walker of St. Louis, at the time the

retiring president of the association and an investment banker, thought it

would be a good idea to establish a tournament similar to the Davis Cup in lawn

tennis, which was established in 1900. He donated an outsized sterling silver

trophy, which he commissioned Tiffany & Co. to hand craft. The three-foot

tall cup (which is engraved with the name “International Challenge Trophy” on

it) is awarded to the winner of the biennial event.

Walker was

the founder of the investment firm G. H. Walker & Co., which was

headquartered at No. 1 Wall Street. As befitting a man at the top of the heap,

he was a member of the best clubs including the National Golf Links of America

in Southampton. He was also a member of the Links in New York City, a

private club established by Charles Blair Macdonald in 1916 whose focus is

promoting and conserving the best interest and true spirit of the game of golf.

It was during a meeting at the Links with the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of

St. Andrews that the idea took root.

In his 2008

history of the Bush family Jacob Weisberg describes George H. Walker as a

“Midwestern prince” whose privileges included a personal manservant and his own

nurse. He developed an affinity for golf while attending a Jesuit boarding

school in England. A very successful (described as brusque) banker, he helped

finance the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. When he moved to New York to set up

his investment firm he was backed by Harriman railroad money and lived in a

mansion on Madison Avenue, and later, at one of the toniest addresses in the

metropolis: 1 Sutton Place. He also owned estates on the North Shore of Long

Island and in Santa Barbara, California, in addition to a ten-thousand-acre

hunting lodge in South Carolina. Both he and his wife had their own chauffeured

Rolls-Royces. In addition to being the benefactor of the Walker Cup, George established

the “Walker’s Point” estate, the family’s 176-acre compound in Kennebunkport,

Maine.

The Walker

Cup was established during an era when amateur athletics occupied a more prominent

position than it does today, especially among pastimes pursed by the rich: the

America’s Cup in yachting, the Newport Cup in polo, and the Davis Cup in

tennis. As originally conceived, the Walker Cup was meant to be a broad

international competition. The original

plan was to have teams from the United States, the British Isles, France,

Canada, Sweden, Italy, Norway, and Spain compete in an “International Golf Team

Championship.” The victorious team would then host the next match in their country.

The idea evolved between conception and the first tournament and it was

launched (and remains today) an Anglo-American tournament, alternating back and forth across

the Atlantic.

The first

match established the congenial tone and sense of good fellowship for the

contest. British and Irish players arrived in New York on the RMS Carmania and were met on the pier by

the president of the U.S.G.A. and then whisked to the posh Hotel Biltmore at

the Westchester Country Club and then to the Links club for lunch. The first

match was contested at C.B. Macdonald’s National Golf Links of America with a match

play format: foursomes (alternate shot), followed by singles matches.

Fast

forward ninety-five years and the best amateurs in the world gather in the

heart of Los Angeles. If those with advantages have a center of gravity in the

city of Angels, a strong case can be made that it is at LACC. The private club

is located smack dab in the middle of the action, with chock-a-block action on

all four points of the compass around them: just to the south are the

skyscrapers of Century City; immediately west is the U.C.L.A. campus in

Westwood; Beverly Hills abuts to the east, and the northern border is shared

with the ritzy Holmby Hills neighborhood and the secluded enclave of Bel-Air. (LACC

is actually located in Beverly Hills, but as discrete aristocrats do, they

understate the case by declaring their residence Los Angeles). For those familiar

with household street names rather than those of neighborhoods, the club is

just south of Sunset Boulevard, slightly west of Rodeo Drive and to the north

of Santa Monica Boulevard, with Wilshire Boulevard roughly separating the club’s

North Course from the South. Like a fertile waystation in a vast desert, LACC

is a 325-acre oasis of green in the sprawling urban hardscape of Los Angeles.

The club occupies arguably the most valuable parcel of contiguous undeveloped

real estate in the country. The captain of the U.S. team, “Spider” Miller,

described it spot on: “It’s like New York, if Central Park was a golf course.”

The fits-like-a-glove clubhouse at

LACC

What does

perfection look like? Well, like beauty, love, or happiness, defining sensibilities

is a tricky proposition. Although elusive to define, the Walker Cup matches at LACC

came as close to being flawless or without defect as can be achieved. For

matters of such weight I find it useful to look to the Italians, who specialize

in such things and have for centuries. They even have their own word for it: sprezzatura. It means effortless grace,

doing something cool with nonchalance. To enter the grounds of Los Angeles Country

Club is to enter a world of privilege. Normally visitors drive up the discrete

entry off Wilshire Boulevard (and with the requisite credentials) pass the

guard gate and drive around to the parking lot. Admission backstage is typically

through the clubhouse. For the Walker Cup, parking was on the South Course

across Wilshire Boulevard. After crossing the busy thoroughfare and walking up the

entry drive, smiling visitors stepped in through a gate near the guard house. Once

behind the hedgerows that run the perimeter of the property, the overwhelming

initial impression is how verdant the rolling terrain is, partially because

there is such a striking contrast against the backdrop of the newly refurbished

white columned clubhouse that stretches out imposingly over the opening and

closing holes.

The

U.S.G.A. does a flawless job of picking courses for the Walker Cup. One of

their secrets (which is hiding in plain sight) is that they select the best

courses ever conceived and built. Since it is a match play event without big

crowds, they have the luxury of selecting courses suited for the format. A

large number of the revered courses they choose were designed during the Golden

Age of golf course architecture. Courses like Cypress Point, the Garden

City Golf Club, and the Kittansett Club. Entering the cloistered setting of

LACC it becomes immediately clear that the guardians of the game did well

picking this venue. Wholly consistent with a tournament started by a patrician and

aristocratic investment banker with both an office and a residence at the

premier location on the street, George Walker would approve of this location

for his tournament.

The golf

course was designed by George Thomas, Jr., a Philadelphia native with his own

patrician background. Born into a wealthy banking family, he attended an

Episcopal prep school and the ivy-clad University of Pennsylvania. Like George

Walker, Thomas was an investment banker in his early days. Thomas moved to

Beverly Hills in 1919 and (as a sideline) designed a respected collection of

golf courses. Although the Riviera Country Club is his most widely recognized

design, his handiwork at LACC was when he reached his apex. Nicknamed “the

captain,” he served with heroism in the First World War as a pilot, having been

shot down three times. Thomas was a real Renaissance man. In addition to his

world-class abilities as an architect of golf courses, he was also a

competitive dog trainer, fisherman, and yachtsman. One of his lasting legacies

was his work in commercial rose hybridization, an area he wrote several books about.

When you walk through the club entrance one of the compelling facets that draws

you in is the long narrow bed of perfectly manicured, multicolored roses that

showcase the varieties he developed. Just like us, the roses apparently like

the dry, sunny, and humidity-free conditions of Southern California. The

subconscious mind makes a quick note: bubble has been entered. One no longer

inhabits the latticework of freeways and urbanity that defines L.A. Behind the

gates of LACC, the mind and body relax; life has switched from black to white

to full technicolor; all five senses are awakened.

The showcase of roses in front of

the clubhouse

I stood

near the clubhouse and practice putting green for a full thirty minutes upon

arrival, simply soaking in the atmosphere of the club, the spectacle of the

Walker Cup environment, and the beauty of the rolling terrain framed by the

Santa Monica Mountains in the distance. Waiters and waitresses clad in

formalwear stood like sentinels on the Reagan Terrace of the clubhouse (the

40th President was a member), the LACC flag fluttering high above the scene,

below the flag of the California Republic and the host nation. Golf cognoscenti

and industry insiders were milling about in anticipation, as were many of

golf’s dignitaries, including the rule makers of the governing bodies. Excited

spectators entering the property for the first time marveled at the

conditioning of the fairways and greens. It was a brilliant, warm day to be soaking

it up. Members were out in abundance in their crested jackets, as proud as a

parent beaming at their child’s graduation ceremony, strutting around between

the clubhouse and the pro shop. The members were easy to identify in their blue

blazers with the red, white, and green LACC crest proclaiming their place in

the world the same way the denizens of Washington Avenue wear their green

jackets in April.

One of the

elements that makes the Walker Cup so special is the unfettered access you have

to the club. On my prior two visits to LACC I was unable to buy anything with

the club emblem on it because the pro shop accepts neither cash nor credit

cards. A purchase requires that it be put on the member’s account, which makes

it more than a bit awkward, their intent that it serves as a deterrent working

as planned. Not so at the Walker Cup, so I took full advantage of the

opportunity. Unlike professional golf events, the Walker Cup does not have

grandstands for spectators. They don’t need any because the crowds are small and

you are free to walk essentially anywhere you want (even on the greens if you

so desire, although that is bad form) as long as you don’t obstruct play. Only a

few areas are roped off, chiefly so you don’t interfere with the players’

ability to walk on or off a tee or green. I took the opportunity to follow the

morning practice rounds, following the U.S. team, who were warming up in two

groups of five. What a thrill to be able to stand on the fairway less than 10

feet behind a player to watch them go through their pre-shot routine, and to

hit the ball. The ten players on each team are among the best amateurs in the

world. They play a different game than you or I do (maybe not you, surely me).

The torque and flexibility they have at such tender ages is a joy to watch,

inducing just a twinge of envy. It is a marvel to see how they consistently hit

the ball long and straight: “Far and sure” as early practitioners of the Royal

and Ancient game called it.

The other

impression I had of the competitors was how young they were. In the Walker Cup

program produced for the 2013 matches held at the National Golf Links of

America, Anthony Edgeworth describes the matches as a “timeless continuum.” His

double entendre of the competition and the players resonates: “The perpetual

youthfulness of the Match, its rosy-cheeked visage reappearing unwrinkled and

optimistic every two years” rings so true. These young bucks have so much

talent and promise, and it was apparent by the looks on their clean-shaven

faces that they knew they were lucky to be playing on one of the games

unrivaled courses in an environment of hushed tones. It is a thing of beauty to

be able to appreciate them up close.

White

pants after Labor Day? A fashion faux pas

in the real world, but we left that when we turned off Wilshire Boulevard. At LACC

the U.S. team was sporting spotless trousers the color of freshly fallen snow. Each

of the players wore a snug crimson baseball-style cap adorned with a blue “W.”

Lithe young collegians, they pulled it off without a hitch because they have sprezzatura; their poised looks as

effortless as their swings. In a stark contrast to the professional game there

was no clutter: no Waste Management or Bridgestone logos on the shirts, nothing

to mar their pristine uniforms or golf bags. Nor were there advertisements on

the caddie bibs. A compelling part of the tradition of the matches is that the

players take club caddies. The local loopers were wearing white bibs and white

hats with the LACC logo on them and based on their smiling and sturdy faces

they understood that participation was an honor.

After

watching the warmup rounds, I took the occasion to walk the course from

beginning to end, alone. The peacefulness and solitude of the environment is a juxtaposition

to the frenetic environment outside the club’s perimeter. Mostly, it was a joyous

walk of solitude. The only sounds making it through the bubble were very L.A.:

the occasional whirring of helicopters swooping around the vast city overhead.

I walked on tee boxes and down fairways in a dreamy state imagining how I would

hit my shots if I were playing. I had forgotten how dry the environment in

South California is. The low humidity levels and desert-like landscape creates a dry and dusty milieu. The air was scented by eucalyptus and ancient sycamore

trees, their gnarled trunks rising from dry river beds were a reminder that

this is a style of golf quite distinct from that played in the wetter Northeast.

I had equally forgotten how hilly the terrain is on the course. After the gentle

opening par five, the long second hole opens up a stretch culminating on the

eighth green that is simply breathtaking. It is as good a stretch of holes as

you will find on any golf course the world over, over a uniquely hilly terrain.

Thomas used the barrancas (Spanish for gully, canyon or ditch) and sloping hillsides

to route a masterpiece, achieving perfect form and harmony with the environment.

Leonardo da Vinci attained sprezzatura

with his perfectly proportioned “Vitruvian Man.” George Thomas’s achieved the

same with LACC’s North Course.

The sharply rolling terrain of

LACC’s North Course as seen on the sixth fairway

An

especially poignant part of the Walker Cup is the flag raising ceremony at the conclusion

of the practice rounds, the day before the official matches begin. The setting

for the flag raising at the 46th Walker Cup was the first fairway of the North

Course, the very place where these young phenoms would be hitting their tee

shots the next morning. A dais and three flag poles were set about fifty yards

down the fairway with spectators kept a respectful distance away. The hatless

players were arrayed on either side of the dais lined up in a row of white

chairs wearing their newly-minted blazers. Off to the right was a collection of

distinguished jacket wearers, each identified by their distinctive emblems, sitting

in their own cluster of white chairs. Any club that has hosted a Walker Cup is

asked to send a representative to the match. Among them there was a gentleman

sitting in a green jacket that had a crest with a thicket of grass and a red

wicker basket poking up through it (Merion), a gentleman with two linksman on

his jacket, a symbol borrowed from old Delft tiles. He was accorded extra

respect among the jacketed group because his club hosted the first Walker Cup

in 1922, at the National Golf Links of America. A ruddy faced gentleman with a regal

logo featuring a harp with a crown over it (Royal County Down) sat smiling

through the proceedings. This was the General Assembly of golf’s inner circle.

I stood

among the well-coiffed ticket-holders and waited the twenty minutes or so that

it took for the members and other luminaries to gather. The gathered coterie was

in all their sartorial splendor, for the club was hosting a celebratory mixer

immediately after. Virtually everyone standing in the fading afternoon light

could be featured in a commercial for a fashion or fitness product. I personally

find it irritating to watch television advertisements by drug companies, which

feature idealized people. I always think, these are fabrications; normal people

aren’t that fit or good looking or well dressed. Nor do they exist in the

scripted, perfect settings that have been conjured up for them. These are just

projected images of perfect people that don’t exist. Except they do, at LACC,

and they were all at the Walker Cup with carefree looks, exhibiting panache without

effort. Cary Grant epitomized sprezzatura,

and pulled off an impeccable look every time he appeared on screen. So too did

the gathered crowd at LACC, wearing their cocktail party best.

Where the

scene had the sharpest contrast and the most poignancy was among the kids.

Privileged teenagers (and pre-teens) stood among the crowd wearing perfectly

pressed slacks, loafers, crested club jackets, pocket hankies, and designer sunglasses,

looking all the world like the mini moguls that they are. I suppose it

shouldn’t be a surprise, this is Southern California after all, and they no

doubt grew up on diets of bean sprouts, avocados, and kale, with almonds as

snacks after yoga. The English golf writer Bernard Darwin, grandson of the

famous naturalist, was famously called upon to play in the first Walker Cup

when a member of the British team became ill. Natural Selection is still alive

and well, as exhibited by the vitality of the establishment at the flag raising.

To paraphrase Cecil Rhodes's comment about the English, "To be a member of

LACC is to win first prize in the lottery of life." The gene here pool is

quite strong.

To kick

off the gala a Marine band marched out stiff-backed in their crisp dress

uniforms, adding

further

dignity to the proceedings. They began with upbeat patriotic songs played at

just the right pitch in the background as wispy clouds scattered high up in the

azure sky. They would in turn play the national anthem of Ireland, followed by

that of Great Britain, as the tricolour and Union Jack were raised in

succession. Finally, the American national anthem was played as the Stars and

Stripes were hoisted. The president of the U.S.G.A. then spoke, followed by the

executive director of the U.S.G.A., the president of the R & A, and the

president of LACC. Each had their respective blue jackets on with their

identifying patches (a circle with an eagle in the center for the U.S.G.A. and the

image of St. Andrew holding the saltire inside a championship belt topped with

a crown for the R & A).

The

highlight of the proceedings were the opening comments of Bush 43, who spoke

with sincerity and wished both teams his best, with a special emphasis added

for those competitors from Texas. George is the namesake of the cup-giver, as

he would no doubt call his great-grandfather. He had lunched with the U.S. team

and described them, in his usual laconic and choppy style, “Good upright citizens. Good

people.” It was he who called the Walker Cup “One of the greatest sporting events

ever,” and it really struck me as true.

The two-day

matches themselves are a throwback to old school match play golf. The morning

foursomes matches were conducted without fuss. The players got up to the ball

and hit without undue analysis and thinking. Their uncluttered minds appear freer

than those of professionals and most recreational golfers. Chalk it up to

confidence and ability. From time to time while following a match, I would

stand on the tee box to watch the first player drive the ball. If I didn’t walk

at a good pace, I almost missed his playing partner hitting the second shot.

They would reach the ball, figure out the yardage and pull the trigger: golf as

it was meant to be played, without equivocation. The gifted golfers hit their

shots with only a smattering of fans following along in deferential silence.

There was a sense of reverence and respect that only the Masters comes close to

replicating, although here the scale is smaller and the overall experience is

better because you are standing in the thick of the action.

The golf

played was of the first order and it was a joy to watch the players walk the undulating

terrain with purposeful, confident strides. Although there is little fanfare,

the event is consequential, since there is no greater honor than to play for

your country. The players are competitive and want to win, but there is no

sense of it being overdone. The knowledgeable fans were ecumenical in their

praise; the visitors were accorded as much respect for good shots and putts as

the home team. There were no chants of “U.S.A.!, U.S.A.!” or other overt displays

of rooting, simply polite applause and discrete encouragement. Yelling at the

Walker Cup (“mashed potatoes,” “get in the hole,” or “you ‘da man”) would be met

with the same enthusiasm as shouting “fire” in a crowded movie theater. The brainless morons who infect other

tournaments stay away because their fate here for such offenses involves

voltage. While the penalties for such behavior are not explicitly spelled out I

would suspect first offenses are punished by being hit with a Taser from a

lurking highway patrolman. I also wouldn't rule out of consideration that second offenses are met by death in the electric

chair.

California’s Highway Patrol

standing by as needed at LACC

The

Masters carefully describes those that make the trek to Augusta as patrons, not

fans. In a similar vein, the Walker Cup does not have fans either. In the leadoff

to the program from the 2013 Walker Cup held at the National Golf Links of

America, certified WASP, honorary chairman of the club and the event, and former

chairman of Morgan Stanley, the late S. Parker Gilbert, addressed his opening

letter to: “Friends of Amateur Golf,” which hits the nail on the head. Those

that make the effort to come and follow the matches love the amateur game. Like

at the Masters, small details are not overlooked: LACC was thoughtful in its concessions

for visitors, included making British and Irish fans feel at home. The lunch selections

included bangers and tater tots as well as Guinness and Smithwick’s on tap.

Even

though the event was staged in a city of four million people, there were

inexplicable so few spectators that at times it felt like a private exhibition

match for LACC members. On more than one occasion walking along with the players

or standing near a putting green I felt like an interloper unintentionally

eavesdropping on their private conversations. Without an inkling of boasting

the end-of-summer chats advised how a family had just returned from their

second home in Montecito, or from a trip to Catalina, and that the youngest

daughter had just returned to Stanford. The membership here is an impressive

lot, a concentration of C-suiters, creators, owners, and rule makers in the

land of Teslas.

Oh yes, I

forgot to mention the Americans won the matches handily, but that is beside the

point. Respected golf writers on both sides of the Atlantic have for years sung

the praises of the matches and captured the essence of what I experienced. From

the British Isles, Michael McDonnell: “In the modern winner-at-all-costs

climate the Walker Cup is an anachronism because winning and losing are never

taken too seriously and at times seem downright irrelevant.” Herbert Warren

Wind added, “There is no explaining how it happens, but a singular atmosphere

develops on these occasions.” The Walker Cup is about the competition and not

the results.

Credit to

the U.S.G.A. for selecting LACC as the venue and for setting the course up in a

traditional manner. There were no tricked up greens, narrowing of fairways, or

other unnatural changes made. They recognized that the course is near

perfection as it is and had the wisdom not to do much.

The rolling swaths of

green create an oasis in the middle of the mega city

Admittedly,

my sample size is small, having attended Walker Cup matches at only the National

Golf Links and LACC, however, based on my experiences at both I would have to

agree with 43 that this is undeniably one of the greatest sporting events ever.

Ticket prices are cheap ($40 for a practice round and $75 on match days), it is

uncrowded, held on the best venues, and the golf is world class. Match play is

also a better spectator format than stroke play. Match play is not as good a format

for television and therefore the contemporary game is dominated by stroke play

events, which is a shame because the ebb and flow of match play is so much more

exciting and unpredictable. While there are other world-class sporting events,

namely Royal Ascot, Wimbledon, the Tour de France, a Notre Dame home football

game, the races at Saratoga Springs, and the Masters, the Walker Cup is just a

cut above because of the intimacy of the affair.

To me the

Walker Cup goes beyond golf and represents one of the few remaining bulwarks holding

the line against our societal race to the bottom. Like the Masters, it is a

beacon of civility in a world with a multitude of disruptions and a systematic lowering

of standards. The cup serves a dual role: not only is it a great sporting

event, but it showcases and upholds a tradition of politeness and decorum that

is waning in our increasingly vulgar and coarse world. Call me an elitist, a

snob, or someone with a serious case of WASP envy, but I soaked up the clean

cut, polite, and learned environment of the Walker Cup with zest. It is a soothing

tonic from a world of sweatpants, cargo pants, ripped jeans, tattoos, and nose earrings.

There is nothing garish, brash, or tawdry about the affair; no doubt it is

because the events are held within bubbles with a different stratum of society

in attendance, however, this is the traditional role of the aristocracy,

ensuring high standards are kept up. Good character trumps trendiness. The

keepers of golf are doing well as they remain the protectors of the traditions and

good manners that golf was founded on.

I find it

enlightening to speculate about what a time traveler would make of all this. Bobby

Jones was a young collegian when he played in his first match after studying

mechanical engineering at Georgia Tech, while he was on his way to Harvard. He

competed in the first five tournaments and his record was 9-1. Imagine if Jones

were to come back; which tournament would he most recognize? No doubt the

tournament he created, the Masters, would still look quite familiar, as Augusta

National have held true to his vision. I would think he would also be quite

pleased at how the nature of the Walker Cup has not changed, remaining timeless

and in good taste.

My visits

to LACC have been among the most memorable and truly enjoyable in all my

travels. Kudos to the club for donating all proceeds of hosting the matches to

the Southern California Golf Association to be used in furtherance of growing

the game. While the starry-eyed players may not have chauffer driven Rolls-Royces

or manservants in their future, their future prospects are open-ended given their

talents and stations in life.